INDIANAPOLIS — More than two years into the coronavirus pandemic, health experts are looking to the future of the pandemic.

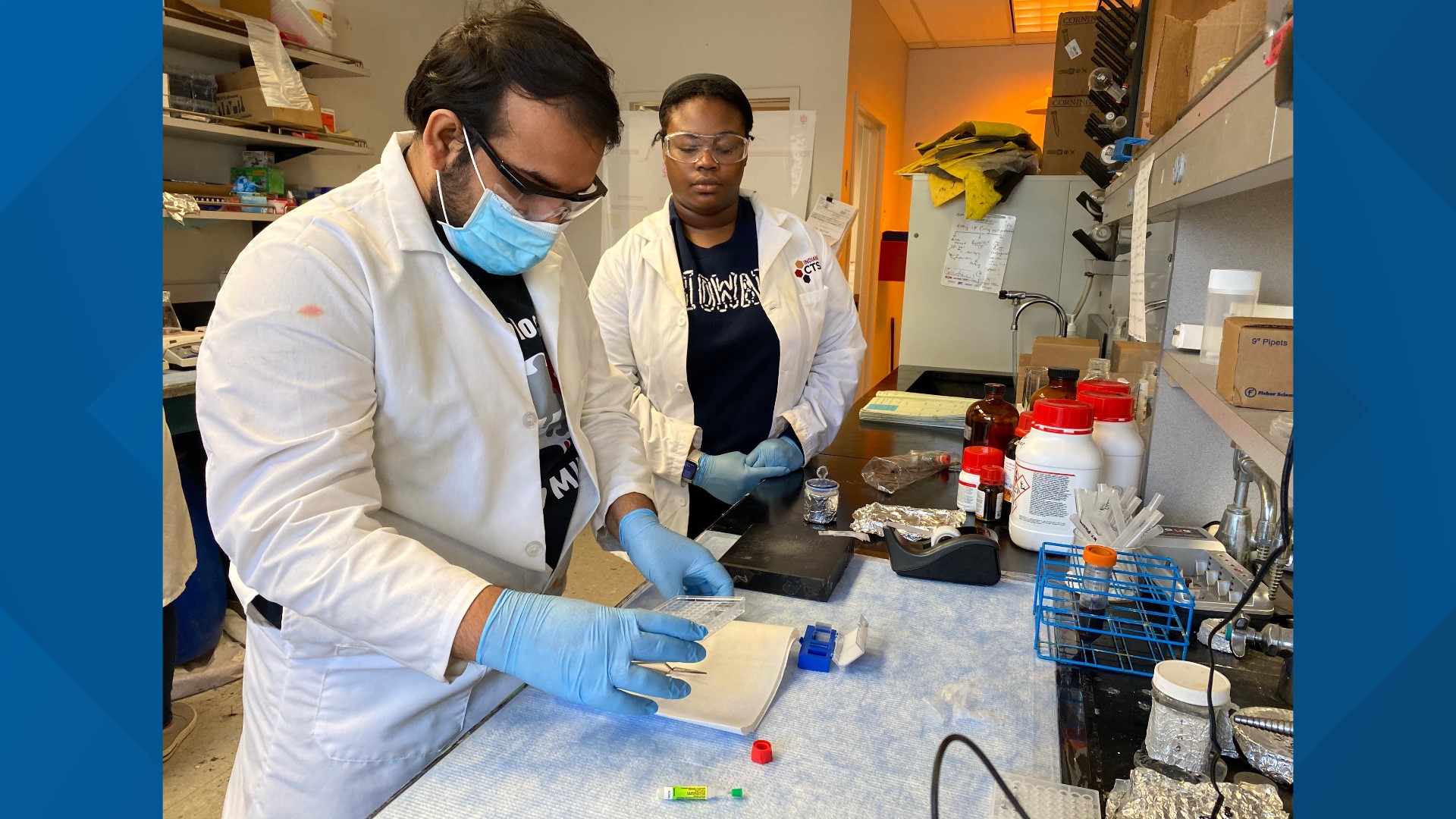

At IUPUI, a small group of students and staff are spending the summer in the lab, finalizing a project years in the making.

The team is building a one-of-a-kind coronavirus biosensor.

Associate Professor of Chemistry and Chemical Biology Dr. Rajesh Sardar leads the project.

"In terms of COVID research, we really want to make it more impactful to the society," Sardar said.

Sardar's team created its first sensor just months into the pandemic. It tested for both the virus and antibodies.

"After that, I think the research became very personal to me, because I lost a cousin who was in his early 30s. He was so young. He's in India, and I heard that news, and we grew up together," Sardar said. "I couldn't believe he is no (longer) with us. Then I thought, 'Okay, the COVID research has to be even more applied, and it has to reach the people.'"

With that inspiration, the researchers took the project up a notch. They implemented a 96-well panel, testing nearly 100 samples at a time.

"We designed our sensors in such a way that is very sensitive, and it is very specific to COVID-19," Sardar said.

However, that size of panel is not enough to test a "population scale" quickly, according to Sardar.

"If we make the test cheaper, then everybody can use it," Sardar said. "How we can make it cheaper, if you can make many tests, spending very a limited amount of resources. I'm talking with a dollar amount."

That's when IUPUI researchers bumped up the project again. They took it from a 96-well panel to 384.

Sardar said the 384-well panel produces more results faster, compared to the 96-well panel, because the larger panel has smaller wells. That means it requires less time to scan each well.

According to school officials, the system only requires 10 microliters of blood to run the test. By comparison, a typical blood panel order collects 10 milliliters of blood, which is more than 1,000 times more than the 384-well panel.

Omolade Olofintuyi is a Brownsburg High School graduate. She now studies Health Science at Howard University, but is spending her summer with Sardar as a part of the research team.

"In high school, I was very involved in a lot of science-based classes, science-based clubs, extracurriculars," Olofintuyi said. "Growing up, I always knew I wanted to be a doctor."

"I've been able to make my own plates and read them as well, just to be able to know what kind of results I'm getting with the ones I'm making," Olofintuyi said.

Sardar said this kind of technology has been around for 30 years, but not without a couple problems.

For one, it has never had enough sensitivity.

"Second is, nobody has made any sensors which can measure so many patient samples at once," Sardar said.

Those human plasma samples are donated by Indiana Biobank, through a partnership with the IU School of Medicine.

"There is precision that is needed," Olofintuyi said. "There is a lot of discipline needed in this lab as well, and I definitely think Dr. Sardar has helped me in learning that this summer."

Olofintuyi will be a second-year student when she returns to Howard University this fall.

"I would love to see this research go far," Olofintuyi said. "It is a blessing for me to have been chosen out of the hundreds of applicants that applied to be a part of this program."

Sardar came to IUPUI in 2010 after spending time at other universities across the country.

"When I came here to give my interview," Sardar said. "I just loved the environment. It is very collegial. Everybody was very warm and just very welcoming during my time."

Sardar is originally from India, where he finished his education. Then, he decided to come to the United States to pursue his PhD.

"It's kind of a dream to come here and work at a big university," Sardar said.

After 12 years of teaching at IUPUI, Sardar said his favorite part of the job is working with students.

"They are the future of this nation, so we need to nurture them and give them the best opportunities as possible," Sardar said.

Sardar said years of students have helped build the detailed design of the latest COVID-19 biosensor, including a former graduate student named Adrianna Masterson, who launched the research in 2020.

The research team has a patent for the biosensor, according to Sardar.

Sardar said this project would not be possible without the IUPUI School of Science, his department and department chair, former students and Indiana Biobank.

What other people are reading:

- Indiana Rep. Jackie Walorski, 3 others killed in Elkhart County crash

- Details released on procession route, how to pay respects to Elwood Officer Noah Shahnavaz

- 'Days of Our Lives' moving to Peacock Sept. 12

- Heartbreak after abortion: Indiana women reflect on emotions after procedure

- 'He told me he loved being a police officer' | Elwood mural to be dedicated to fallen Officer Noah Shahnavaz

- Chick-fil-A in downtown Indianapolis to open Aug. 4

- Indianapolis ventriloquist advances to live shows on 'America's Got Talent'

- Edwards Drive-In working exclusively from food truck after January restaurant closure