She was gone for 88 minutes and came back to a heartbreaking discovery. Her 10-year-old was dead.

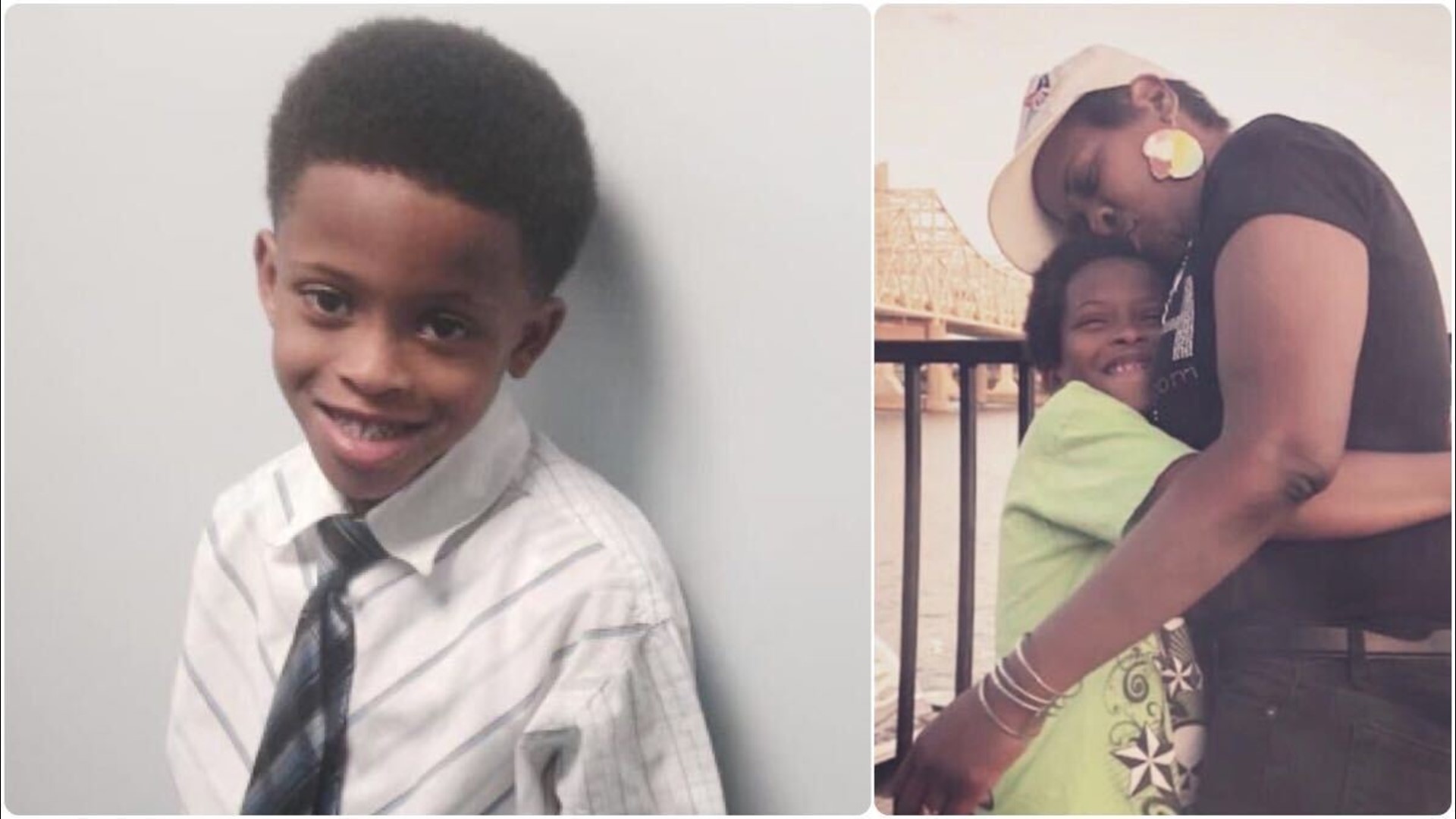

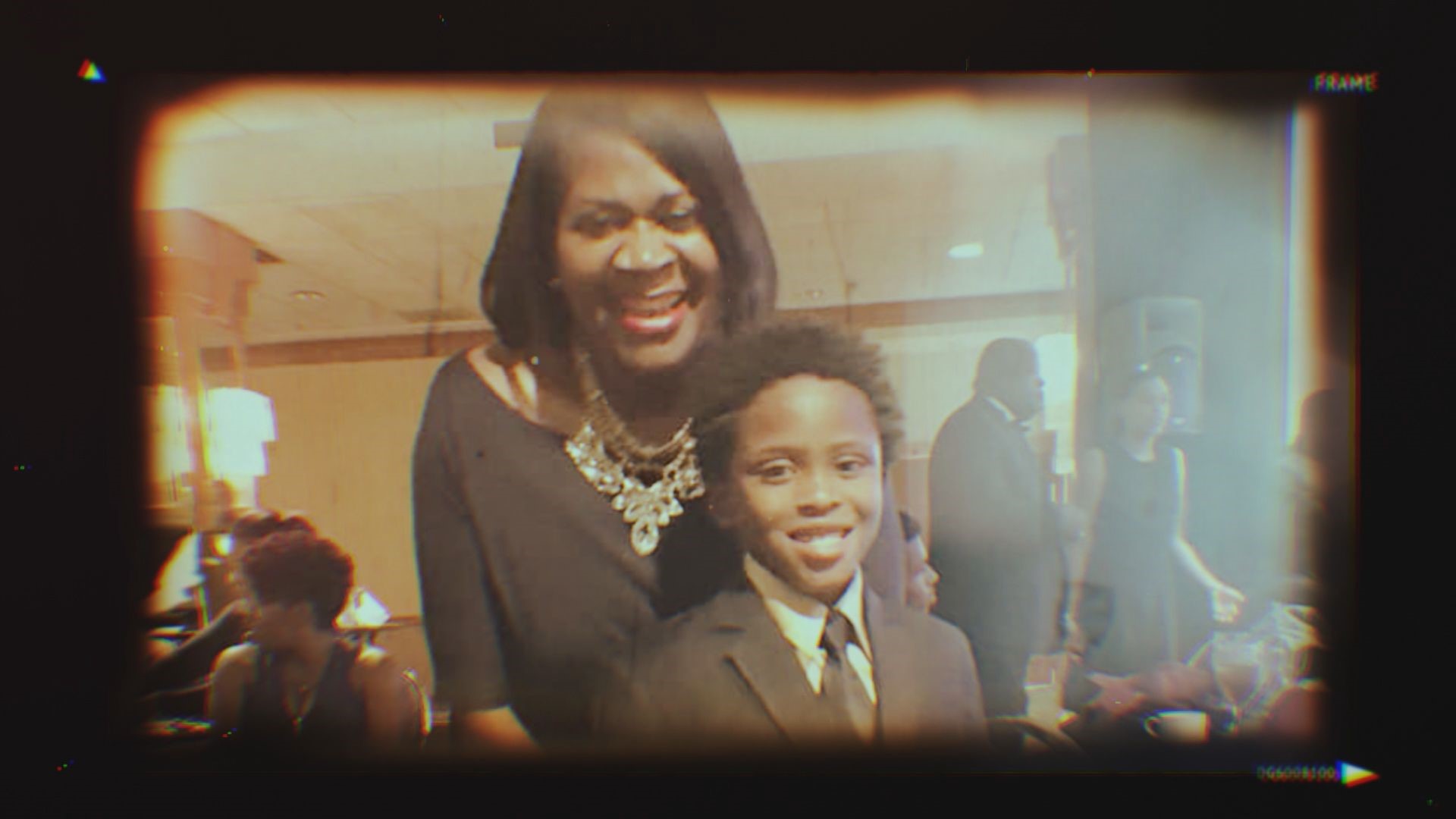

Tami Charles' son, Seven Bridges, died by suicide in 2019. She said the bullying he encountered resulted in his death.

Editor's note: This story contains racist language and graphic descriptions of death by suicide involving children. If you or someone you know is struggling with thoughts of suicide, help is available. Call the National Suicide Prevention Line at 1-800-273-8255.

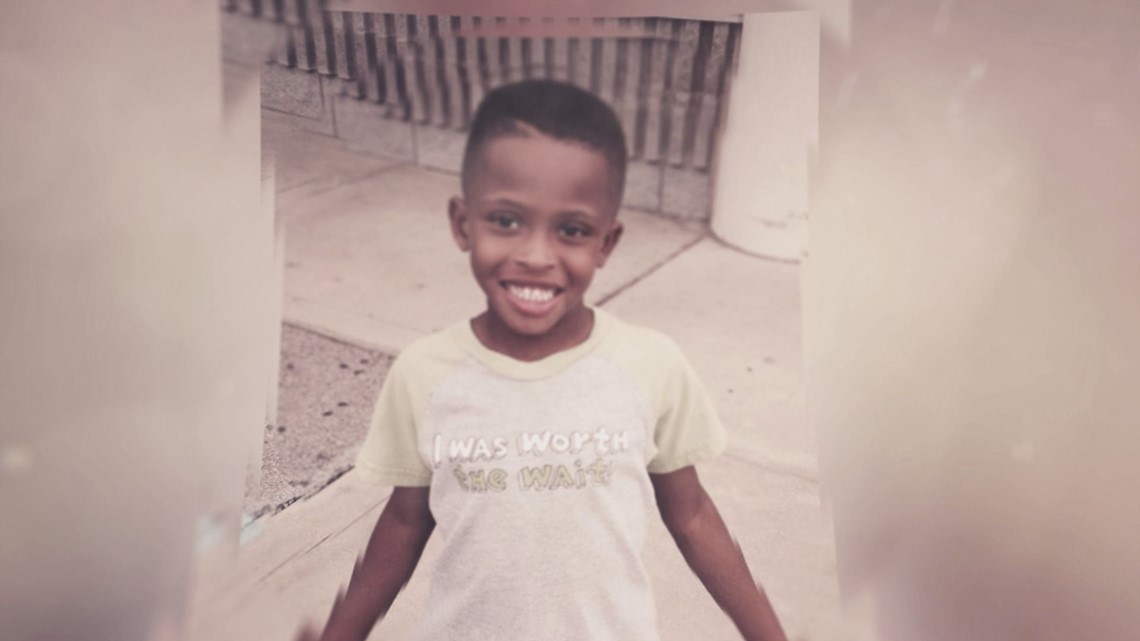

Tami Charles was often told she couldn't have children -- but her "miracle child," Seven Bridges, made her life complete.

"Seven being the number of completions, seven being God's perfect number," she said. "But more than anything that I raised him on was --- how many times do you forgive your enemy? Seven times 70."

"I treated him like he was a miracle and that he was loved every single day," she said.

Charles said when Seven was a little boy, he wanted to be a superhero.

"I knew that he was a gift and that is why he was so exposed to so many things... I have seen the world," she said. "I just took my time to see it again through his eyes."

But her miracle child's life was cut short. She said bullying is to blame.

In the first episode of the series "A Different Cry," Charles shares her son's story.

When it all began

School started in August 2018, and for the first time in Seven's life, so did bullying.

"The very first thing, a little girl called him a [N-word] on the bus," his mother said.

"And then, fast forward to next week, he's on the bus and the little girl says, 'well, you know, that [N-word] can't fight,'" Charles added. "That was on a Friday. On Monday, he gets off the bus... runs to his dad and says, 'Daddy, I get choked on the bus, but don't be mad because I think he has a mental problem.'”

Situations similar to Seven's happen in classrooms across the country. According to the U.S. Department of Education, 37% of Black students report being bullied based on race, English proficiency, or disability.

Alfiee Breland-Noble, youth psychiatrist and founder of The AAKOMA Project, said it's important for parents to take action if they know there is a problem.

"If your child is coming home talking about bullying, you have a duty to get yourself up to that school and get it taken care of -- if you have to scream, holler, pound on tables," Breland-Noble said.

"If they're complaining about it, go up to their school and demand it at school, do something," she said.

Charles did just that. She documented her efforts in online social media videos that went viral. She also said she was an active parent who volunteered and would go to Seven's school on average twice a week for lunch.

"It broke down the false security that I had, that I am this involved, they see me this much and for that, maybe my kid would have some sort of exception," Charles said.

She said she fought for her son repeatedly. Seven also went public with his fight against bullying.

'I can still make friends with him'

In Sept. 2018, 11Alive's sister station, WHAS11 in Louisville, Ky., talked with Charles and her son about some of the bullying he was experiencing at school.

“I still can't get him choking me out of my head,” Seven said at the time. He was in the 5th grade.

He said he told a friend about the incident where another student called him the N-word. His friend told him to beat up the student. But when Seven refused to do so, he said his bus buddy started choking him.

The district told WHAS11 the bus driver did address the situation, saw no sign of injury, and filed an incident report the next day. The school district said it was conducting an investigation.

In an interview with 11Alive, Renee Murphy, the then-chief communications and community officer for Jefferson County Public Schools said children are safe in the district.

"We stand with our students and with our staff to support them and to make sure that we have a welcoming environment for everyone that's in our buildings," Murphy said.

She said they've also done different reviews in the past into how investigations are conducted. Murphy said they individualize cases involving physical contact.

"We have the people in place with our bullying prevention team that can review complaints and concerns with families and they work with our schools to resolve those matters," she said.

Documents also show that during the bus incident, Seven was put in a headlock and other children were screaming during the incident. The bus driver had to pull over. The district called the incident "horse play." According to the student handbook, horseplay is defined as the following: “Student(s) is/are engaged in roughhousing, pushing, running, excessive play, etc., that are not appropriate or safe in the school environment.”

In the WHAS11 story, Seven, who was only in the 5th grade at the time, wanted to respond with kindness.

“I know that I can get it out of my mind, and tomorrow is like a better day, so I can still make friends with him.”

That was Seven's final message to the world. Read more of the WHAS11 story here.

'Bullied to death'

Charles said it was 77 days in between the first time her son was bullied and the day he died by suicide. He was 10 years old.

"He died of being bullied to death," Charles said. "Wow, my kid."

The Kentucky native wasn't the only student enrolled in Jefferson County Public Schools in the 2018-2019 school year to die suicide. Reports indicate there were nine of them. The district has a student population of roughly 100,000.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that at least 3,600 children under the age of 13 died by suicide in the last two decades.

Holly Wilcox, a suicide researcher and professor for Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, has seen many families impacted by the jarring suicide rates.

"We definitely, in our hospital system see people as young as 7, 8, 9 years old who are presenting to our hospital with thoughts of suicide," she said. "Whether or not they fully understand that death is final is another whole question."

"I don't think sometimes that kids understand there's no coming back from this -- this is much younger children," said Breland-Noble.

According to the Journal of the American Medical Association, young Black children are dying by suicide at rates two-times higher than their white peers.

"People always say Black people don't do that. Yes, here's a picture," Charles said.

Research shows bullying and racism are tied to many of these suicides.

"I never took the time to teach my son about racial differences, racial inequalities," Charles said. "I never did that because he was 10. I want this little boy to be a little boy."

88 minutes

Jan. 19, 2019 will be a day Charles will never forget.

"I was gone for 88 minutes. I'm beating on a door, you know how it is, 'boy come out and get these groceries out this car!' I’m beating on the door and I figured maybe he'd fallen asleep again," she said. "I beat on the front door, beat on the side door, couldn't get in. I had to go back to the church and get my husband's key."

Charles said once she came inside, she looked all over the place for her son. Seven was a "jokester," so Charles said she thought that maybe he was hiding.

Then, she then made the heartbreaking discovery.

"Something said, 'look over my shoulder, in his room.' And there my baby was with his back to me. I grab him around his waist, and I say, 'Boy, why would you do this?'"

"I remember, saying out loud, 'God! Why my son? Why my son?' And I heard, just as clear as I'm talking to you, very nonchalantly put, 'I gave my son.' I promise you, the words that I heard," Charles recalled.

Charles hopes that sharing Seven's story will help other families. She is also launching advocacy efforts to provide awareness about suicide and bullying.

WHAS11 has done extensive coverage on Seven and the school district. Their recent report talks about the changes that have come since the 10-year-old's tragic death and his legacy.

A DIFFERENT CRY: Watch the full series

Family believes school bullying contributed to son's death: 'My baby just was pushing everything in'