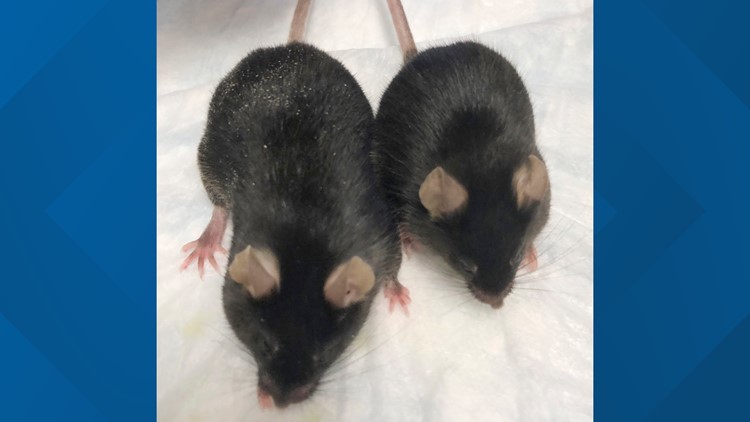

Bulked-up, mutant "mighty mice" held onto their muscle during a monthlong stay at the International Space Station, returning to Earth with ripped bodybuilder physiques, scientists reported Monday.

The findings hold promise for preventing muscle and bone loss in astronauts on prolonged space trips like Mars missions, as well as people on Earth who are confined to bed or need wheelchairs.

A research team led by Dr. Se-Jin Lee of the Jackson Laboratory in Connecticut sent 40 young female black mice to the space station in December, launching aboard a SpaceX rocket.

In a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Lee said the 24 regular untreated mice lost considerable muscle and bone mass in weightlessness as expected — up to 18%.

But the eight genetically engineered "mighty mice" launched with double the muscle maintained their bulk. Their muscles appeared to be comparable to similar "mighty mice" that stayed behind at NASA's Kennedy Space Center.

In addition, eight normal mice that received "mighty mouse" treatment in space returned to Earth with dramatically bigger muscles. The treatment involves blocking a pair of proteins that typically limit muscle mass.

A SpaceX capsule brought all 40 mice back in good condition, parachuting into the Pacific off the California coast in January. Some of the ordinary mice were injected with the "mighty mice" drug after returning and quickly built up more muscle than their untreated companions, Lee said.

The scientists completed the experiment just as the coronavirus was hitting the U.S.

"The only silver lining of COVID is that we had time to write it up very intensively" and submit the results for publication, said Dr. Emily Germain-Lee of Connecticut Children's Medical Center, Lee's wife who also took part in the study. Both are affiliated with the University of Connecticut.

While encouraged by their findings, the couple said much more work needs to be done before testing the drug on people to build up muscle and bone, without serious side effects.

"We're years away. But that's how everything is when you go from mouse to human studies," Germain-Lee said.

Lee said the experiment pointed out other molecules and signaling pathways worth investigating — "an embarrassment of riches ... so many things we'd like to pursue." His next step: possibly sending more "mighty mice" to the space station for an even longer stay.

Three NASA astronauts looked after the space mice, performing body scans and injections: Christina Koch and Jessica Meir, who performed the first all-female spacewalk last fall, and Andrew Morgan. They are listed as co-authors.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.