INDIANAPOLIS — Where you live should not determine how long you live. Yet, in metro Indianapolis, there are stark differences in life expectancy.

If you live in Fishers, you're expected to live 84.8 years, but travel 17 miles south and you'll arrive in John Kelly's neighborhood on the near east side of Indy, where life expectancy drops to 68 and could go lower, according to a recent report from the Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health at IUPUI.

Kelly is 57 years old and, during the pandemic, had periods of time without his medicine for diabetes.

"It was really hard. I started to notice this difference. My eyesight got blurry, my hands and feet would swell and I didn't feel well," Kelly said.

Kelly represents many living in distressed areas where the pandemic only made it worse.

"We don't know yet the impact of COVID on life expectancy in these neighborhoods, but it's likely to widen, given what we know about COVID," said Courtney Robert, director of Social Impact: Global Health Equity Partnerships at Eli Lilly and Company.

Before COVID, back in May 2018, Eli Lilly announced it would partially fund the Diabetes Impact Project, DIP-IN, which is led by IU's Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health in partnership with Eskenazi Health, which also provided funding, as well as the Marion County Public Health Department, Local Initiative Support Corporation and The Polis Center.

The collective goal is to improve diabetes management for those living with diabetes and increase awareness of diabetes to encourage more people to get screened so they can act.

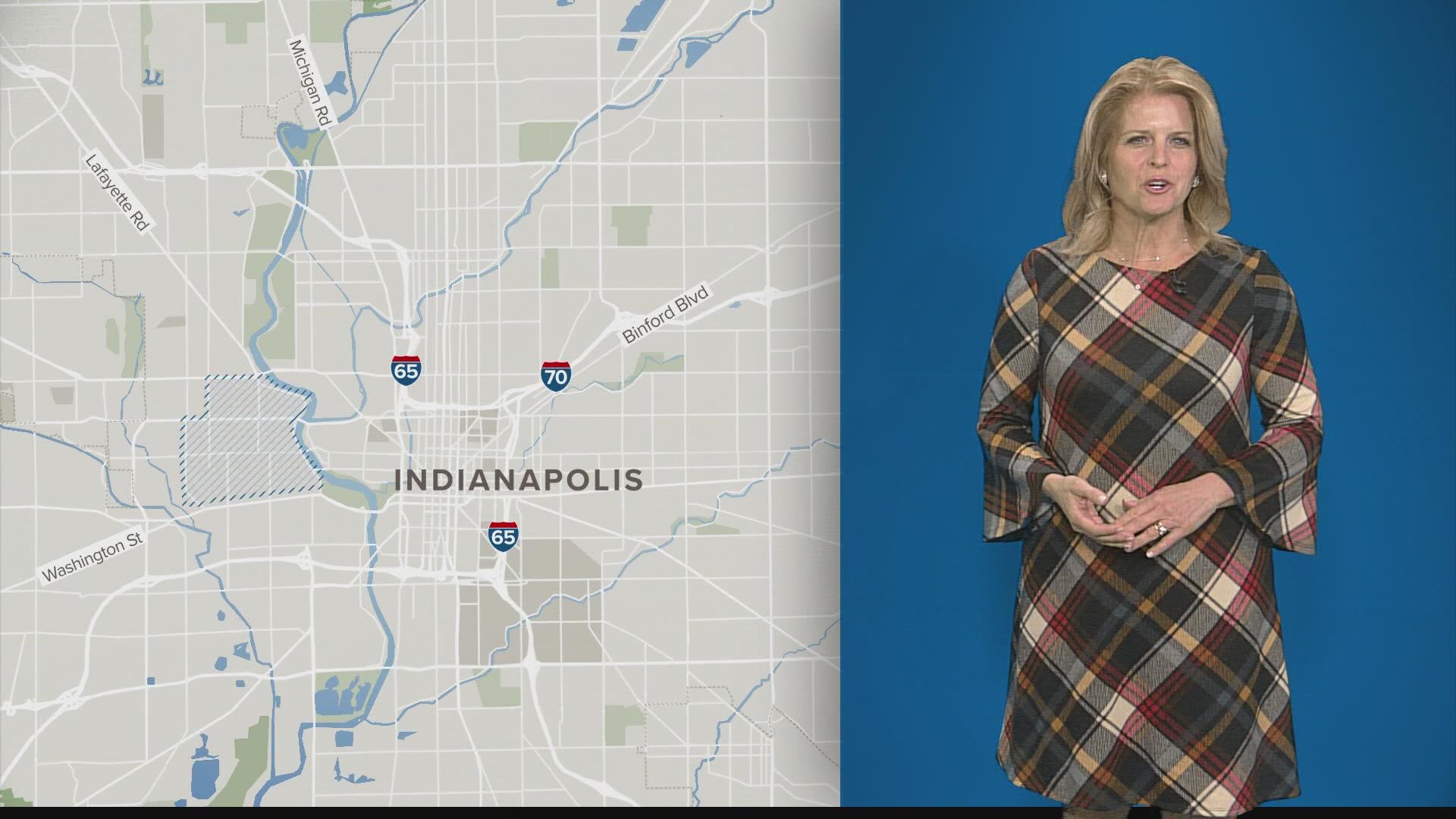

The target locations are the neighborhoods in the northeast, northwest and near west areas of Indianapolis, including the ZIP codes 46202, 46205, 46208, 46218, 46222, 46226 and 46228.

These are urban communities of color with twice the national obesity rate and an estimated 20% have diabetes. The global average is 9%.

When DIP-IN launched, the life expectancy gap in central Indiana was 14 years. The latest data from the Worlds Further Apart report shows the gap has now grown to 16.8 years.

“I think all of us that live in Indianapolis can say that number is shocking. And it doesn't need to be that way,” Roberts said. “Diabetes is not something that has to be a terminal illness. It's a manageable condition.”

This fall, Lilly accelerated its investment, adding another $5 million to DIP-IN. The money will fund even more community health workers like Shakata Norwood, who visit patients at home. Six of the workers are funded by Lilly, three are funded by Eskenazi Health.

“I know if I go to the doctor and I know I'm coming for high blood pressure, diabetes, hearing, I'm gonna put on my best, my best dress, and I'm gonna tell the doctor what he wants to hear. So, with that, community health workers, we can see behind the doors we can see behind the scenes, and we understand the true struggle and we can help,” said Norwood.

Norwood works out of Eskenazi's Forest Manor Health Center in the northeast Indianapolis neighborhood and since connecting with Kelly, his diabetes is under better control.

“I got my A1C level down to 8. I'm off the insulin and I'm taking the Metformin twice a day,” Kelly said.

Norwood said she’s finding better health outcomes after helping create a better life.

“I'm coming to your house and I want to talk to you about diabetes, and you are on the verge of getting evicted. You're not gonna want to talk about your diabetes, you're not even gonna care about if I'm taking my medicines. So my thing is to reach you in a way to where you understand that, 'let's figure out A and then we can go to B,'" Norwood said.

Norwood said patients will pay more attention to what they eat when they aren’t worried about if they’ll eat. That’s why earlier this year, she delivered boxes of food to Kelly’s home and helped him get the best price for his medicine.

“People go through things and it's not our job to judge, it's our job to help,” Norwood said. “Being able to control your diabetes, you're able to get up, you're able to get out, do more, do more things outside, and have a longer life.”